Uncategorized

Uncategorized

Why does the space competition work?

Randall Perry March 30,2018

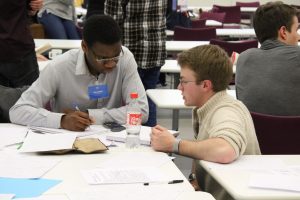

I am often asked why the Space Design Competition (SDC) format works. Whilst my quick fire response when in the throes of organising an event is often, “It’s all the students’ own work, not ours”; this does belie the research and development that underpins the setting up and running of the events run by the SSEF.Whether taking place in our competition for younger students, the Galactic Challenge (GC) has been tailored for 10 -14 year olds), or the hallmark senior competition, the Space Design Competition for those up to the ages 15 – 18, students’ become enthused by the event, and surpass expectations of their teachers and parents. The SDC and GC present participants with a problem that is challenging enough so that they need to apply (metacognitive) strategies to monitor and achieve success, but not so challenging that they become overwhelmed. The provision of mentors that facilitate students to recognise problems and thus achieve solutions is key to SDC and GC methodology. Mentors will encourage planning and monitor the progress throughout the day, but will not give specific answers; rather they will facilitate the students to solve their own questions. In addition to the confidence students acquire from taking part in a competition, they gain soft skills from working in a large team, and self-belief from presenting their completed work, and answering questions from a panel of expert judges. Further development of all these acquired skills beyond the competition is a given.

Many of the underlying principles have been introduced to SDC competitions come from work and research I have completed with Catherine Twomey Fosnot. The following edited excerpt is from the introduction of a chapter we co-wrote in 2005.

Excerpt from Chapter 2 introduction – Constructivism: A Psychological Theory of Learning by Catherine Twomey Fosnot and Randall Stewart Perry – you can click on the link above to read the chapter in its entirety*

Psychology – the way learning is defined, studied, and understood—underlies much of the curricular and instructional decision-making that occurs in education… Behaviorism is the doctrine that regards psychology as a scientific study of behavior and explains learning as a system of behavioral responses to physical stimuli. Psychologists working within this theory of learning are interested in the effect of reinforcement, practice, and external motivation on a network of associations and learned behaviors. Educators using such a behaviorist framework preplan a curriculum by breaking a content area (usually seen as a finite body of predetermined knowledge) into assumed component parts—“skills”—and then sequencing these parts into a hierarchy ranging from simple to more complex. Assumptions are made that observation, listening to explanations from teachers who communicate clearly, or engaging in experiences, activities, or practice sessions with feedback will result in learning; and, that proficient skills will quantify to produce the whole, or more encompassing concept… Further, learners are viewed as passive, in need of external motivation, and affected by reinforcement; thus, educators spend their time developing a sequenced, well structured curriculum and determining how they will assess, motivate, reinforce, and evaluate the learner. The learner is simply tested to see where he/she falls on the curriculum continuum and then expected to progress in a linear, quantitative fashion as long as clear communication and appropriate motivation, practice, and reinforcement are provided. Progress by learners is assessed by measuring observable outcomes—behaviors on predetermined tasks. The mastery learning model is a case in point. This model makes the assumption that wholes can be broken into parts, that skills can be broken into sub skills, and that these skills can be sequenced in a “learning line.” Learners are diagnosed in terms of deficiencies, called “needs,” then taught until “mastery”—defined as behavioral competence—is achieved at each of the sequenced levels. Further, it is assumed that if mastery is achieved at each level then the more general concept (defined by the accumulation of the skills) has also been taught. It is important to note the use of the term “skill” here as the outcome of learning and the goal of teaching. The term itself is derived from the notion of behavioral competence. Although few schools today use the mastery learning model rigidly, much of the prevalent traditional educational practice still in place stems from this behaviorist psychology. Behaviorist theory may have implications for changing behavior, but it offers little in the way of explaining cognitive change—a structural change in understanding. Maturationism is a theory that describes conceptual knowledge as dependent on the developmental stage of the learner, which in turn is the result of a natural unfolding of innate biological programming. From this perspective learners are viewed as active meaning-makers, interpreting experience with cognitive structures that are the result of maturation; thus, age norms for these cognitive maturations are important as predictors of behavior… Further, the curriculum is analyzed for its cognitive requirements on learners, and then matched to the learner’s stage of development…

Rather than behaviors or skills as the goal of instruction, cognitive development and deep understanding are the foci; rather than stages being the result of maturation, they are understood as constructions of active learner reorganization. Rather than viewing learning as a linear process, it is understood to be complex and fundamentally non-linear in nature.

Constructivism, as a psychological theory, stems from the burgeoning field of cognitive science, particularly the later work of Jean Piaget just prior to his death in 1980, the socio-historical work of Lev Vygotsky…The remainder of this chapter will present a description of the work of these scientists and then a synthesis will be developed to describe and define constructivism as a psychological theory of evolution and develop.

Continue to read full chapter

*From a book Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives, and Practice. Editor Catherine Twomey Fosnot